It’s no secret that I am a lover of the short story form, and I like to think that I have garnered a pretty good reputation as a short story writer, and that readers enjoy my work as much as I enjoy producing it. I’ve crafted many stories I’m proud of, and I’m grateful that a good few of these have achieved something for me, either in terms of publication or doing well in competitions. Other stories, ones I’d swear are the best material I’ve ever produced, have yet to find a home. There may be many reasons for this, up to and including me being deluded about my own genius. Yeah, I know, but humble servant of art that I am, it still does happen from time to time!

And yet…

For all the successes I’ve enjoyed to date, there is a place I’ve yet to reach with my writing. It’s something I know when I see it, and I am determined to bring my craft to that level, mainly because I feel an artistic imperative to do so, but also so I can hopefully place some stories in my dream publications. It’ll happen some day, I know it will, and with each new story I create, I am edging closer to it. I’ve received a number of tiered rejections from those publications, so I’m at least knocking on their doors.

I’m currently reading a book called Short Circuit, which is a collection of essays on the art of the short story, edited by Vanessa Gebbie. I picked it up in the pop-up bookshop in Doolin when I was at the UL Creative Writing Winter School, and the content has proved to be quite excellent.

The first essay, by Alison MacLeod and entitled Writing and Risk-Taking, is all about (not surprisingly) taking risks with our writing. Specifically, she refers to writing about taboo subjects. Fetishes, that sort of thing, and it got me thinking about how and why I take risks with my writing, and why it’s important for me to keep pushing the limits of what I write about. Perhaps even more important is to challenge what I give myself permission to write about.

Sure, I’ll take risks with form and language, and I’ll address important issues such as dementia, dying, grief and sexual trauma. But writing about actual sex? No, so far I’ve mostly skirted around it, and it makes me wonder, why do I shy away from what is a most human and intimate act? Is it due to my Irish Catholic upbringing, or could it be that I fear I won’t get it right? Possibly, it is both, yet I must somehow overcome these hurdles, because if this artist isn’t willing to write about the things she finds hard to write about then she’s failing in her task.

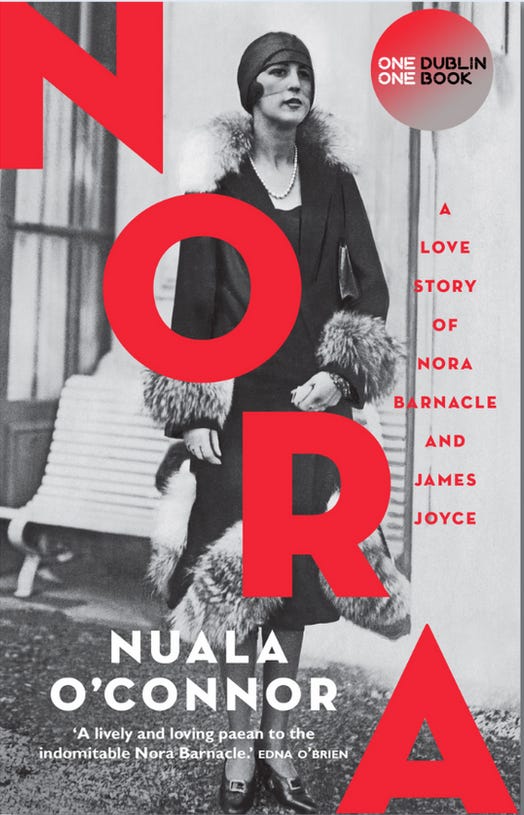

Writing about sex can be erotic without being raunchy, and can be glorious rather than gaudy. To take an example of how it can be achieved in the most beautiful fashion, I turn your attention to the wonderful novel Nora (New Island Books, 2022) by Nuala O’Connor, who in my opinion is one the finest Irish writers of her, or any, generation.

No one writes about sex and sexuality better than Nuala. Her approach to it is as tender as it is visceral, as lyrical as it is muscular, rendering the most intimate moments in vivid shades through the musicality of her prose.

The following is from the opening of Nora, and is used with the kind permission of the author.

MUGLINS

Dublin June 16, 1904

WE WALK ALONG BY THE LIFFEY AS FAR AS RINGSEND. THE RIVER SMELLS like a pisspot spilling its muck to the sea. We stop by a wall, Jim in his sailor’s cap, looking like a Swede. Me in my wide-brim straw, trying to throw the provinces off me.

‘Out there are the Muglins Rocks,’ Jim says, pointing out to sea. ‘They have the shape of a woman lying on her back.’

His look to me is sly, to see if I’ve taken his meaning. I have and our two mouths crash together and it’s all swollen tongues and drippy spit and our fronts pressed hard and a tight-bunched feeling between my legs. His hands travel over my bodice and squeeze, making me gasp.

‘Oh Jim,’ is all I can manage to say and I step away from him.

‘You have no natural shame, Nora,’ he says, and he’s coming at me now with his thing out of his trousers and in his hand, that one-eyed maneen he’s no doubt very fond of. It looks, I think, like a plum dressed in a snug coat.

‘No natural shame?’ I say. ‘Don’t be annoying me. Do you think because I’m a woman that I should feel nothing, want nothing, know nothing?’ But I dip my nose to his neck for a second, the better to breathe his stale porter, lemon soap smell. Span-new to me.

Jim squints and smiles. I kneel on the ground before him, my face before his tender maneen, glance up at him; Jim drops his head, the better to see my mouth close over it. The taste is of salt and heat, the feeling is thick and animal. I suck, but only for a spell, then I draw back and peck the length of it with my lips. I stand.

‘There,’ I say, ‘there’s a kiss as shameful as Judas’s and don’t tell me it isn’t exactly what you wanted, Jim Joyce.’

Such wonderful prose, and such a beautiful, intimate scene; what Nuala manages to show us in this brief and powerful passage is astonishing. The playfulness of the characters, their teasing of each other, is so true to life. Nora’s willingness to pleasure James, his coy way of asking for it, her understanding of his unspoken desire, speaks deeply not only of their physical intimacy, but also of their deep and enduring emotional bond. These characters totally love each other, and I can only imagine that the great James Joyce, himself a fearless artist, would wholeheartedly approve of how Nuala has depicted him and his beloved Nora Barnacle.

Let me ponder this a bit more deeply.

In any story, we have characters, and they interact with each other as people do. We have dialogue, movement, momentum. Language is of course of huge importance, and should be an experience in itself, but there can be many levels to a story. Though I might slip into my characters’ skins to some degree, I must ask myself, am I willing to go all the way in like Nuala does, and really occupy their lives? When my female protagonist goes to bed with her lover, must I fade to black, or gloss over the details? If I am to reveal who she truly is to the reader, surely no better way exists than to show her in the most intimate of exchanges.

It matters, it really does, that we take these sorts of risks with our writing, that we challenge ourselves and our readers, that we draw as close as we can to our characters. In doing so, we can discover who they are, and also who we are.

To paraphrase Alice, the one who followed a tardy white rabbit into Wonderland, I don’t know what I think about a thing until I write about it. To stretch the idea a bit further: in the film The Matrix, Neo follows the girl with the white rabbit tattoo to a nightclub, where he meets Trinity, and she brings him to meet the enigmatic Morpheus, the man who will free his mind.

I too must follow the white rabbit, and discover where he will lead me. I must free my mind and creativity from the barriers that I and my life experiences have set for it.

I must become my own Morpheus.

To this end, I have an idea for a new short story that I’ve been tinkering with for the last week, and it is currently stewing somewhere between my amygdala and hippocampus. This story involves matters of an unusual sexual nature, and very specifically so. In part, I’m letting the story stew because I’m not yet willing to take the risk of writing it, but here and now, I am setting myself a challenge, to complete it by the end of the holiday season.

It’s time for me to be brave and get intimate with my characters, and to do so in the sort of style that Nuala O’Connor excels at.

This is the secret sauce, the deep dive into the hearts and souls of my characters that my writing needs right now.

I must be unafraid.

No need to look first.

I’m just going to jump.

Check out my interview with Nuala O’Connor, in which she touches on some of the matters discussed in this post.

Jennifer, we grew up in 1960's and 70's Ireland, where talking about sex brought red faces and giggles. Think of any reading where sex is explicit or nodded towards? The behind the hands embarrassment and cringe is akin to watching Nine and a Half Weeks with your mother. An author once told us in class that effectively the only thing worse than bad sex is someone writing about it. I suppose bad sex should be defined as consensual and between two adults, but uninspired and cold in it's execution. Fair dues to you, completing your task over Christmas!!