HIGHLY COMMENDED

in the Frazzled Lit Short Story Award 2025!

Listen to Geraldine reading her story:

Twenty-one is a tender age. Not that you realised that at the time. No, you forged ahead, seeking adventure, wanting to get away. With your BA under your belt (your Dad asked what BA stood for, your mother said ‘bugger all’...) With your newly-minted degree, you landed an admin job in the east of France, not an hour from the Swiss border.

You loved answering the phone. You’d rattle off ‘Bureau des Relations Internationales’, and allow the torrent of the caller’s French to sweep over you, picking out key words, repeating what you’d understood, checking for holes in meaning. You loved getting the list from the boss, Jacques, every morning, and ticking off the tasks one by one throughout the day. You hated filing, but got better at it as time went by. A necessary evil. So things wouldn’t get lost. Or mislaid.

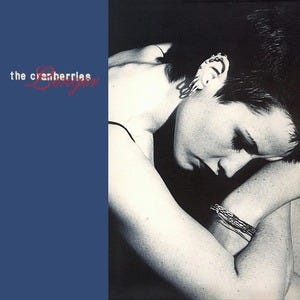

Louis was your colleague, a laid-back French guy, who gently smiled when you made mistakes, most famously when you declared ‘Je suis une Slave’, while wanting to say ‘I am a slave’. But he also got you out of linguistic landmines when dealing with irate students. There was a kind side to him, like when he bought you The Cranberries latest CD. He said your accent reminded him of Dolores O’Riordan’s. Maybe all Irish accents were the same to him. All French ones were certainly the same to you, though he teased that you were acquiring the Franche-Comté slow drawl. Maybe you were. Unknown to yourself.

The job was 9-5, Monday to Friday, but you were flat out, submergé. The office could have done with more staff, but Jacques was miserly and preferred to hire sparingly. You went to lunch with Jacques and Louis in the college canteen every day, where everything was served with cous cous (far from it you were reared), and you used to finish off the meal with a tiny crème brûlée and an espresso like rocket fuel. Jacques and Louis enjoyed your stories of Ireland (they might have been embellished, or they might not – but the aim was to entertain).

One Friday evening, Louis said he was going over to Switzerland the next day to visit his grandmother, and would you like to go with him? You hesitated, knowing he had a girlfriend, a leggy blonde who sometimes stalked into the office, and glared at you with narrowed eyes. As if reading my mind, Louis said:

‘Oh, Isabelle is working tomorrow. I’ve told her I’m inviting you. She said it would be a chance for you to do some sightseeing.’

You knew this didn’t sound like anything Isabelle might say, but you were sick of your apartment on the outskirts of town. It was up three flights of stairs, with no lift, and there was little source of entertainment, except for the tiny téléviseur in the shared kitchen. Your flatmates were a mixed bunch – Japanese, French and American. The more you all minded your own business, the better things worked out. So you told Louis you’d go on the trip, and he said he’d pick you up the next morning at 8.30.

You went to the boulangerie first thing for pain au chocolat and bottles of water, so that you and Louis could have a mid-morning snack in the car. Switzerland was renowned for being expensive, and what Jacques paid wasn’t going to make millionaires of anyone. Louis arrived at 8.30 on the dot (as punctual as the French buses, he was). As you drove out of Besançon, he put on a CD, some French singer with sad-sounding songs, and you settled into a semi-comfortable silence.

As you approached the Swiss border an hour later, it was like entering a Christmas card. Snow-capped mountains, winding roads, lakes as big as oceans. He drove for another thirty minutes and then pulled up on the shores of Lake Neuchâtel, an expanse which reminded you of the sea at home on a calm day. As you poked in your bag for the pain au chocolat, tears stung your eyes. You thought of all you’d left behind – parents, friends, your dog, PJ. You rubbed your eyes furiously, before Louis could notice. But Louis was no daw.

Next thing, his arms were around your shoulders, and he was moving in for a kiss. His woody aftershave was overwhelming up close, like the scent of millions of pine needles. Nevertheless, you turned your head to meet his lips, and in that kiss everything dissolved – the stress of living through a second language, of keeping up with Jacques’ demands, of being away from home. Louis smiled then, and though you tried to read his expression, it was impenetrable.

Your mind racing and your body tingling, Louis dropped you in Neuchâtel and he headed off to his grand-mère’s nursing home, which he said was out in the countryside. You strolled around the city, admiring the perfect houses with their shuttered windows, and in the background evergreen trees dotted the horizon. After a while you succumbed to temptation and stopped at a café for an espresso and a croque-monsieur. Although April, it was warm enough to sit outside on one of the wooden fold-up seats. An elegant old lady sat opposite you, her hair coiffed high in a bun, her poodle on the seat next to her, equally well-groomed. The lady smoked Camels like her life depended on it, one after the other, the smoke rising in curls. Anyone would think she was on a film set. What a pity you couldn’t ask her for advice. She looked like a woman of the world. She’d know what to do if her colleague had made a move on her.

You didn’t know how to manage your guilt, especially as you felt the kiss was the best thing to have happened to you in ages. But if it was the best thing, then why did you feel so cheap? And what would happen next? You ordered a second coffee from the waiter – it wasn’t as if you were going to sleep much that night anyway. A plan formulated in your mind. You’d root out your TEFL cert from the bottom of the suitcase and drop a CV into the private language school. They were always looking for extra tutors. Going back to Ireland wasn’t an option. You’d only be met with a chorus of ‘I told you so’s’ from Mam and Dad.

You met Louis outside the Hôtel de Ville as planned, and let Dolores O’Riordan do the singing on the way back in the car. You thought you’d never get back to your apartment, to the sulky flat-mates and that crumby téléviseur. Louis drummed his hands on the steering wheel in time to the music and smiled away to himself, that enigmatic little smile.

‘See you Monday,’ he said, as he dropped you off. Totally nonchalant, as the French would say. Not a bloody bother on him, as they’d say at home.

Whenever you hear The Cranberries now you think of him, and all the complicated feelings rise up, like the waves on Lake Neuchâtel on a windy day. He and Isabelle got engaged that summer. You moved to the International Language School, where the wages were better and the hours shorter. You were far better at teaching than at admin anyway.

Twenty-one was a tender age, and you were learning new things about yourself every day.

Geraldine McCarthy lives in West Cork. She writes flash fiction, short stories and poems in English and Irish, and her work has been published in various journals. Geansaithe Móra, her flash fiction collection, was An Post Irish Language Fiction Book of the Year 2024.